|

|

Campo

Santa

Maria Formosa

|

Church of Santa Maria Formosa

|

We cut across Campiello

Querini Stampalia, go under the sotoportego and we

will be in elegant Campo Santa Maria

Formosa.

The church

of

Santa Maria Formosa was rebuilt by Mauro Codussi at the end of

the 15th century.

Its interior is divided into square sections separated by low columns

and arches, which give the church a human dimension. It contains

two amazing paintings, Santa Barbara

by Palma il Vecchio, and Madonna della Misericordia

by Bartolomeo Vivarini. During a recent visit on a cold December

afternoon, the church was completely packed and several priests, all

dressed in white, were celebrating mass in the Coptic rite.

|

We walk around the

campanile

and on the canal side, above the doorway, we

will see a grotesque sculpture that inspired John Ruskin to say: "A

head - huge, inhuman, monstrous, leering in bestial degradation." As

usual, Ruskin took it too seriously. These grotesque sculptures,

called scacciadiavoli or

scare-demons, were used to keep bad spirits away. Other scacciadiavoli can be found at the

base of the bell-towers of San

Trovaso, in Dorsoduro, and San Giovanni Elemosinario, in San

Polo.

In medical terms, the face on the wall of Santa Maria Formosa seems to

represent somebody who suffered from neurofibromatosis. Campo Santa

Maria

Formosa

is the perfect place to unwind, sit down, have a cup of coffee, read

a book, engage in conversation or just watch people walk by.

|

|

|

Campo Santa Maria Formosa

|

Campo

Santa

Maria Formosa |

|

|

Fondamenta

dei Preti

|

Ponte del Paradiso

|

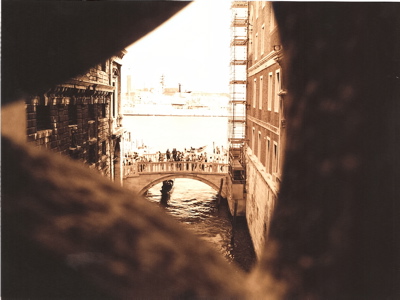

We leave the campo by the

canal side, Fondamenta dei Preti. Before we

reach Ponte del Paradiso, we will see on our right an old funerary urn

inserted in the corner of a building and, across the canal - Rio del

Pestrin-, a beautifully decaying façade pierced by Gothic

windows.

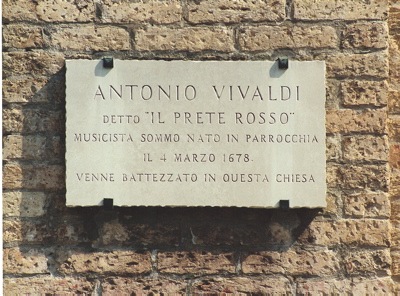

Vivaldi used to live in this building at number 5879. Right across from

the entrance to the building is Ponte del Paradiso topped by a Gothic

arch

and a relief of the Madonna

della Misericordia. Calle del Paradiso is one of the most

charming corners of Venice. It showcases the true commercial spirit of

Venice amidst a medieval ambiance. If we take Calle del Paradiso, we

will end up back

in Salizada San Lio. This detour is worth taking if you are interested

in buying books about Venice. Libreria Editrice

Filippi will be on our left, just before we reach the Salizada.

|

|

|

Gothic

window

|

For many years Vivaldi

lived here

|

|

Rio del Pestrin from

Ponte dei Preti

|

Roman

funerary urn by Ponte dei Preti

|

|

|

For generations, the

bookstore and publishing house Filippi has

specialized on Venetian

themes. It carries a large selection of new titles as well as old books

that are difficult to find elsewhere. Its owners will welcome you and

will make you feel at home.

|

We retrace our steps but

before we leave Calle del Paradiso, we should take a look at one of its

most distinctive features: the wooden barbacane

that protrude from the walls at the second-floor level. This

architectural element, very common in Venice, was used to increase the

living space without obstructing the pedestrian traffic.

We cross Ponte del Paradiso again and walk alongside the canal,

Fondamenta del Dose, that leads to Calle del Dose and Calle de

Borgoloco where we turn right. This will take us to Ponte Borgoloco.

Its wrought iron railing is said to represent an acronym for Viva

(long live) Vittorio Emanuele.

Vittorio

Emanuele, King of Italy, visited Venice in 1866

when the bridge underwent its last reconstruction.

We retrace our steps,

cross Ponte Marcello and we will soon be in Campo Santa Marina.

|

Campo Santa Marina is one

of the few campi

in Venice named after a saint and without a church. The church of Santa

Marina stood at numbers 6067 and 6068 but was demolished in 1820. It is

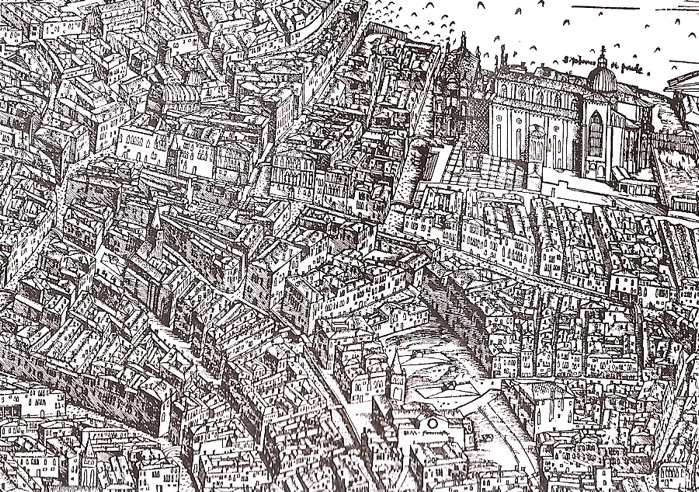

visible in Jacopo de' Barbari's map. Across from the Hotel Santa Marina

is Pasticceria Didovich

(Castello 5909) where you will find a fantastic assortment of pastries

plus some delicious vegetable tarts called salatine. Giovanni Bellini lived in

the parish of Santa Marina. He died on November 29, 1516 and was

buried,

alongside his brother Gentile, in the Scuola de Sant' Orsola, next to

the

church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

|

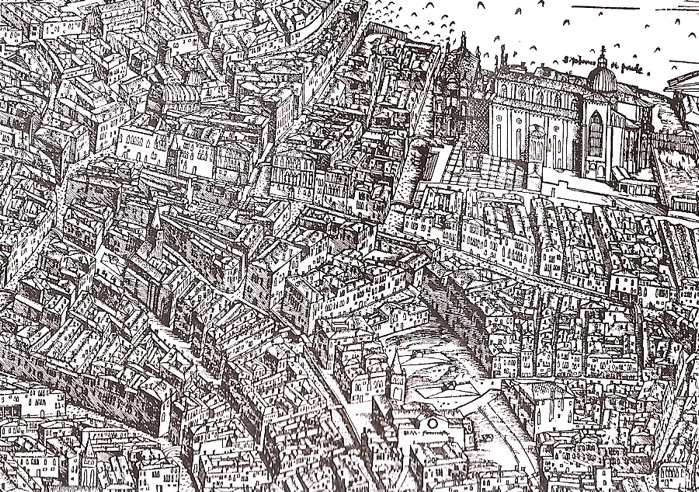

de' Barbari's view of campi San

Lio, Santa Maria Formosa, Santa Marina

and Santi Giovanni e Paolo

de' Barbari's view of campi San

Lio, Santa Maria Formosa, Santa Marina

and Santi Giovanni e Paolo

We exit Campo Santa

Marina by Calle del Frutariol and make a right turn

at Calle de la Malvasia. We continue on Calle

del Pistor where, just before crossing the bridge (Ponte del Pistor),

the

excellent bakery Ponte delle Paste

is located. After crossing the bridge the street will take us back to

Campo San Lio.

|

|

|

Campo

Santa

Marina

|

Campo Santa Marina

|

|

|

Real canoce

|

Marzipan canoce at "Didovich"

|

From Campo San Lio we

take Calle de la Fava that will lead us to the

church of Santa Maria de

la Fava, arguably the only church in the world named after a

legume.

How the church got its name is, like all things Venetian, shrouded in

mystery and the subject of controversy. Most likely the name derives

from the vendors of fava beans who brought their barges and their

business to the bridge opposite the church. In 1496, when the church

first opened as an oratory dedicated to a miraculous image of the

Madonna, the bridge was already known as Ponte de la Fava and the

church as Santa Maria del Ponte de la Fava. Marin Sanudo, the

chronicler of Venice, wrote in his diary on December 16, 1497, that

because of an outbreak of the plague, the Senate had asked the Pope to

postpone his annual Christmas pardon and to close the popular churches

of

"Madonna di Miracoli, San Zuan Crisostomo, San Fantin, and Santa Maria

dil Ponte di la Fava" so as to avoid the congregation of people and the

spread of the disease. The church was rebuilt in the first half of the

18th century. Among its works of art, Giambattista Tiepolo's Education of the Virgin, is the

most remarkable. The official name of the church is Santa Maria della

Consolazione.

|

|

|

We begin our walk in

Campo Santa Marina which we exit by Calle and

Ponte del Cristo. From Ponte del Cristo the dreamlike view is

quintessential Venetian. As we

cross the bridge we enter Cannaregio. We turn right on Ponte de le

Erbe. The next bridge is Ponte Rosso from where we have a great view of

Rio dei Mendicanti and the Scuola di

San Marco. From this bridge, we can also see the last numbers of

the sestieri of Cannaregio

and Castello.

|

|

Scuola Grande di San

Marco and church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo

|

Rio

dei

Mendicanti from Ponte Rosso

|

|

Hidden from view and to

the

right is the church of Santi

Giovanni

e Paolo (San

Zanipolo.) This church is consecrated to Saints John and Paul, two

brothers, two soldiers and two martyrs from the 4th century. Campo

Santi Giovanni e

Paolo is the perfect spot to sit down for a

drink or a cup of coffee. Rosa Salva,

a Venetian institution that offers delicious pastries and savory

treats, is conveniently located just across from the side door of the

church.

|

Campo and church Santi Giovanni

e Paolo

Campo and church Santi Giovanni

e Paolo

Impressive stained-glass windows, a

rarity in Venice, grace the

church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo considered the Venetian Pantheon

because many doges are entombed here. The inlaid polychrome marble

floors are simply stunning.

|

|

|

| This

church is a treasure trove of art and architectural details. The

chapel of the Rosary, accessible through a door at the end of the left

transept is well worth visiting. The beautifully carved wood panels,

end of

17th century, were

originally from the Scuola della Carità. They are the work of

Giacomo Piazzetta and depict scenes from the life of Christ and Mary.

The chapel was damaged by fire in 1867 and restored to its former glory

in the 20th century. The church houses many works by

Pietro, Antonio and Tullio Lombardo and a rare nine-panel painting by

Giovanni Bellini, Saint Vincent

Ferrer, that contains a poignant Saint Sebastian. The former

Scuola di Sant' Orsola, for which Carpaccio's Saint Ursula

cycle was originally painted (now at the Accademia), stood next to the

apse of the church. The Bellini brothers, Gentile and Giovanni, were

buried in this small scuola. The remains of the

Venetian patriots, brothers Attilio and Emilio Bandiera, and

Domenico Moro rest in this church, near the entrance. |

|

|

|

Gentile (left) and

Giovanni Bellini (right) and between them a white-haired man. Detail

from Gentile Bellini's Procession in

the Piazza San Marco.

|

Tombs of the Bandiera brothers and

Domenico Moro

|

The beautifully

sculpted wellhead in the middle of

the campo was moved here in

1825 from its original location in the sestiere of San Marco. At the base, a Latin inscription

reads: "Mira silex mirusque latex

qui flumina vincit" which can be more literarily than literally

translated as:

"Wonderful stone and even more wonderful this water, that surpasses

that

of the rivers."

|

|

|

The

equestrian statue in

the middle of the campo was

designed

by Andrea Verrocchio and shows the mercenary

captain, condottiere,

Bartolomeo Colleoni who victoriously commanded the Venetian

land forces for many years. In his will he left most of his fortune to

the Venetian state on condition that a monument be erected in his honor

in front of San Marco. His wish was granted, almost. The statue was

erected in front of San Marco, the

Scuola not the Basilica

as he had intended. It should be noted that the Venetian abhorred the

cult of personality. In the ten centuries of the Venetian Republic no

public figure had a statue erected anywhere in the city, much less in

Piazza San Marco.

|

The Scuola di San

Marco today houses the Civic Hospital. Its façade, a work of

Pietro

Lombardo

and Mauro Codussi, was recently restored. Get close to the main door

and

admire the amazing trompe l'oeil.

|

On

the main doorjamb, a few inches from the floor, there is a small

drawing, etched in the stone, of a man with a turban carrying a heart

in his left hand. A

terrible story is associated with this etching. According to legend, a

handsome young man, the son of a prosperous Levantine merchant and a

Venetian mother, lived with his father on the Island of Giudecca but

often visited his Christian mother who lived in this area of Castello.

He dressed in the Turkish fashion, like his father, but unlike him had

a hard time fitting into society, feeling rejected by both the Jewish

and the Christian communities. Perhaps as a result of this inner

conflict, perhaps because he was just plain rotten, he mistreated his

mother to the point of violently beating her. But she always forgave

him. One night, he got completely out of control, stabbed her and

ripped her heart from her chest. As he ran away in horror, carrying the

heart in his left hand, he tripped on the steps of Ponte Cavallo, in

front of

the scuola, and fell to the

ground. Then he heard the voice of his mother coming from the heart and

asking: "Did you hurt yourself, my

son?" In desperation, the young man ran to the edge of the

lagoon and drowned himself. A beggar, a stonecutter by trade, who used

to spend the nights by the door of the scuola, witnessed the incident and

made the etching that we see today.

As Venetian as the legend sounds, I

believe this is a dressed-up, local color-added, European tale. I

heard the same

story, minus the turban and the scuola, from my mother's lips as a kid

growing up in Argentina. In turn, my mother probably heard it from her

Piedmontese grandmother. My guess is that a story so impossibly

gruesome is hard

to forget and likely to spread. Despite all, Venice must be the only

place in the world with a graffito

of it.

|

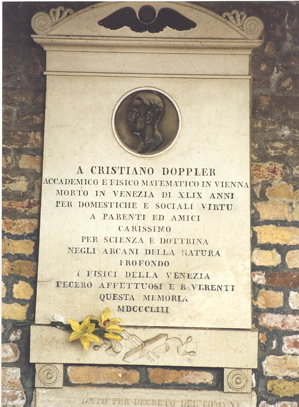

We walk to the Fondamente Nuove, the northern edge

of the city, by the side of the hospital. From there we'll have a

splendid view of the lagoon and the cemetery island of San Michele, the

resting

place of many personalities: Igor Stravinsky, Ezra Pound, Sergei

Diaghilev, Joseph Brodsky and Christian Doppler, among many others. It

was precisely Joseph Brodsky who in his brilliant Venetian reflection " Watermark" wrote the following

words about this corner of Venice:

" I remember one day -the day I had to

leave after a month here alone. I had just had lunch in some small

trattoria on the remotest part of the Fondamente Nuove, grilled fish

and half a bottle of wine. With that inside, I set out for the place I

was staying, to collect my bags and catch the vaporetto. I walked a

quarter of a mile along the Fondamente Nuove, a small moving dot in

that gigantic watercolor, and then turned right by the hospital of San

Giovanni e Paolo. The day was warm, sunny, the sky blue, all lovely.

And

with my back to the Fondamente and San Michele, hugging the wall of the

hospital, almost rubbing it with my left shoulder and squinting at the

sun, I suddenly felt: I am a cat. A cat that has just had fish. Had

anyone addressed me at that moment, I would have meowed. I was

absolutely, animally happy."

|

We return to Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo and exit it by the side of

the

church, Salizada

San Zanipolo, and turn right on Corte Veniera. This will take us to

Fondamenta dei Felzi. From the beautiful iron bridge, Ponte dei Consafelzi, we will have

the perfect view of a most remarkable building,

Palazzo Tetta, that cuts the canal in two like a ship cuts the waters

of the ocean. As you face the palazzo, look up to your right where you

will see an unusual chimney that, for a moment, will make you

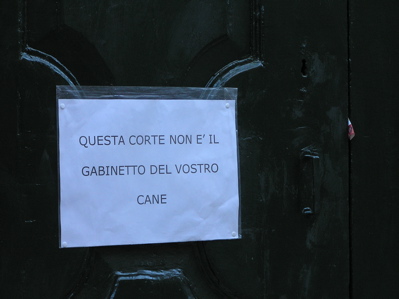

forget that you are in Venice and will take you to the Far East. As I

was wandering in this area of Venice some years ago, I saw a

handwritten sign posted on a front door that

read "Si pregano i signori 'Animali' di lasciare libera la porta dall'

inmondizia (loosely translated as: "We beg the animal gentlemen to keep the

door free of garbage." Like the one at the church of San

Giovanni de Malta mentioned earlier, this

sign

was one of many that I saw scattered

in different corners of the city and I couldn't help but think that for

a republic to survive for a thousand years, diplomacy must

be ingrained in its citizens' DNA. |

Palazzo Tetta on Rio de

S. Giovanni Laterano, left,

and

Rio de la Tetta, right

|

|

|

We take Calle Bragadin o

del Pinelli

that ends at Calle Longa Santa Maria Formosa

where we turn left. You will soon be on Fondamenta and Ponte Tetta.

Unlike its more famous cousin, Ponte delle Tette (in the sestiere of

San

Polo) named after the flashy-fleshy merchandise displayed by the

local prostitutes, the 'Tetta'

of this remote part of Castello refers to the noble family Tetta who

had their residence in the palazzo

around the corner. After crossing Ponte de l'Ospedaleto we will be on

Calle de l'Ospedaleto that will take us to Barbaria de le Tole. To our

left is the ornate façade of the church of Santa Maria

dei Derelitti or 'de

l'Ospedaleto'

(a work by Longhena). This

church, like Vivaldi's La

Pietà, has a long and distinguished musical tradition.

|

The

area around Rio de San

Giovanni Laterano seems like a very remote part of Venice, but don't

let

the absence of tourists fool you. From antique dealers to marble

artisans, they all have their shops here, especially on Barbaria de le

Tole that

soon becomes Calle del Cafetier, at the end of which is Campo de Santa

Giustina or de Barbaria.

In

this campo there is a

small free-standing

building,

the Oratorio

Beata Vergine Addolorata,

one of the few of its kind remaining

in

Venice.

|

|

|

Rio de

S.

Giovanni Laterano

|

Ponte Capello on Rio de la Tetta

|

We take Calle Zon and

after

crossing the bridge, Ponte Santa Giustina, we reach the fondamenta of

the same name. To our right is the scenic Campo Santa Giustina. The

church and convent of Santa Giustina closed in 1810. Today the building

houses the Liceo Scientifico.

We retrace our steps on Fondamenta Santa Giustina and take Calle San

Francesco

de la Vigna, at the end of which we will see half the façade of

the church of San Francesco de la Vigna

designed by Andrea Palladio.

|

|

San Francesco de la Vigna

|

San Francesco de la Vigna, cloister

|

The

church was built using the number three, a reference to the Holy

Trinity, as an important design element. The interior has the splendid

painting by Antonio Falier da Negroponte, Madonna and Child, a stunning

transition piece between the Gothic and the Renaissance styles, as well

as

other works by Giorgione, Vivarini and Giovanni Bellini. The vineyards

after which the church is named are unfortunately closed to the public,

but the cloister is open.

In the background, the

bell tower of the church of San Francesco de la Vigna

In the background, the

bell tower of the church of San Francesco de la Vigna

|

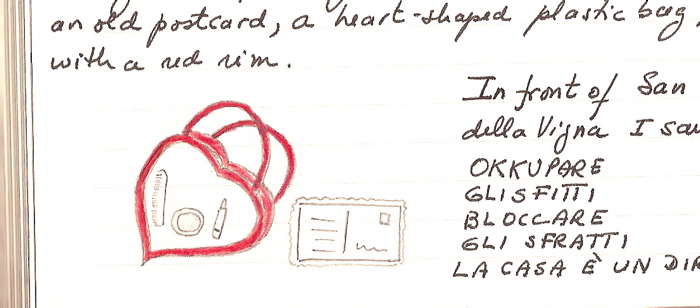

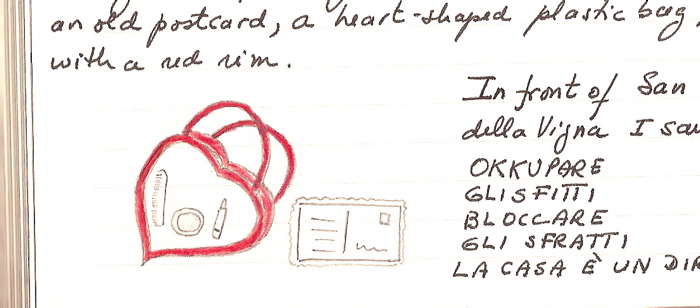

We exit the area by the

side of

the church, Campo de la Confraternita,

where

I

once saw a graffiti that

said:

"OKKUPARE

GLI SFITTI

BLOCCARE

GLI SFRATTI

LA CASA E UN DIRITTO!"

(Occupy the vacant

houses. Block the evictions. Housing is a right.)

And I couldn't help but think how strange that in a place with so many

vacant houses, housing could still be a problem. We follow the street

Corte drio la Chiesa and after a few turns and bends we will be in Campo de la Celestia,

one of the few campi

in Venice that actually has grass.

This area of Venice, behind the

Arsenale, has a number of blocks with relatively new apartment

buildings. In a small corner of the campo

I once saw a ten-year old

girl selling her treasures all lovingly arranged on the pavement

stones:

a postcard, a comb, a pencil, a transparent plastic purse shaped like a

heart with a vibrant red rim and red handles. I couldn't help but think

that for a republic to survive for a thousand years, entrepreneurship

must

have been ingrained in its citizens' DNA. I should have put my

inhibitions

aside and bought that purse.

From Campo de la Celestia we take Fondamenta del Cristo and cross Ponte

del Suffragio o del Cristo and we will be in lovely Campo Santa

Ternita (Holy Trinity). The church of Santa Ternita was

destroyed in

1832. This campo invites us

to sit down and enjoy the

intimate setting: the campanile,

the

chimneys, the beautiful wellhead, the two bridges, the sound of

running water, the color-coordinated laundry hanging from the windows,

and the old ladies peeking from their balconies decorated with wooden

flowers. This is Venice at her best.

|

We

exit Campo Santa Ternita from the opposite side we came in, cross the

bridge and take Calle Donà that leads us to Calle Magno were we

make a right turn. A few yards away is the Sotoportego de l'Anzolo with

a beautiful sculpture of an angel flanked by two hedgehogs (riccio in Italian), the crest of

the Rizzo family.

We reach Campo dei do Pozzi

(Campo of the Two Wellheads) that, despite

its name, has only one. However, it must have had two wellheads

centuries ago, as suggested by the relief on the remaining wellhead.

The relief of the three

angels represents the Holy Trinity (a common iconographic symbol in

Eastern Christianity), a reference to the nonextant church of Santa

Ternita. A relief of Saint Martin is shown on the opposite side, a

reference to the nearby church of San Martino. The

wellhead, in Istrian stone, dates from the 16th century.

Some scenes from the movie Bread and

Tulips were shot in this campo.

We

exit the campo by

Calle del Forno that takes us to Calle dei Scudi where we turn left.

After a few yards we turn right on Calle de l'Arco that will lead us to

Salizada and Campo Sant' Antonin.

|

We

start our walk on Riva

degli Schiavoni by Ponte de la Ca' di Dio. We

cross the next bridge, Ponte de l'Arsenal, and turn left on the

fondamenta. The little grassy area, under the shade of the trees, is

very inviting for a break in the heat of summer, and offers a

postcard view in the dead of winter.

A few years ago, the day

before the Regata

Storica,

held the first Sunday in September, on Rio de l'Arsenal I had a close

view of some of the magnificent boats that would

be on parade the next day, as many of them were moored overnight in

this

area of Venice.

|

Rio de l'Arsenal before

Regata Storica

|

Rio de l'Arsenal before

Regata Storica

|

|

|

Rio de

l'Arsenal before Regata Storica

|

Regata

Storica

|

The Museo

Storico

Navale, on the corner of the riva

and the fondamenta, a few

steps away from

Ponte de l'Arsenal, is worth the visit. Organized in three main floors,

the museum offers a panoramic and detailed view of the maritime history

of Venice from its beginnings to the modern era. One of its highlights

is a scaled-down reproduction of the ceremonial barge, the Bucintoro (a word that may derive

from burcio, a type of

Venetian ship and d'oro,

golden) , which was dismantled

and burnt after the fall of Venice in the hands of Napoleon. It is said

that 400 mules were used by the French soldiers to carry away the gold

recovered from the ship. Recently, the Fondazione

Bucintoro has undertaken the construction of a new Bucintoro at

the

Arsenal. Some of the boats on display on the upper floors of the museum

are so big that the façade of the building had to be demolished

to get them in. This museum is a true gem; there is so much to see that

you should plan a visit in the early morning. The museum is closed in

the afternoon.

|

|

|

|

As we exit the museum we

turn right on the fondamenta

and

walk almost to the end where we cross Ponte de l'Arsenal or del

Paradiso to Campo

de l'Arsenal. In this picturesque campo

we can admire the entrance to

the Arsenal,

which for many centuries was the engine behind Venice's power. Here is

where the Venetian ships were built as early as in the 12th century.

The assembly line was an integral part of the Arsenal's operation

centuries

before Henry Ford, credited with inventing it, put it to use for

automobile manufacture in the USA. The word Arsenal (Arsenal in

Venetian, Arsenale in

Italian) is derived from the Arabic word Dar al

Sina'a, which means workshop. From Venice, the word has passed

into most European languages with a slightly different meaning.

|

|

|

|

Unmistakable symbols of

Venice,

several lions guard the entrance to the Arsenal. The most curious one

is the lion on the

west side of the entrance. It was part of the spoils of war brought by

Doge

Morosini in 1687 from Piraeus (the port of Athens). It has some

Runic symbols engraved on its shoulder, probably the work of a Norse

soldier fighting for the Byzantine emperor in the 11th century.

|

|

Left: The real thing at

the Arsenal. Above: Copy at the Port of Piraeus

|

Dante visited the Arsenal

on two

occasions, in 1306 and 1321. The impression that the place made on him

must have been very strong as the Canto XXI of his Inferno testifies. A

marble plaque on the side of the main portal commemorates this.

As in the Arsenal of the

Venetians, in winter, the sticky pitch for smearing their unsound

vessels is boiling, because they cannot go to sea, and, instead

thereof, one builds him a new bark, and one caulks the sides of that

which hath made many a voyage; one hammers at the prow, and one at the

stern; another makes oars, and another twists the cordage; and one the

foresail and the mainsail patches,—so, not by fire, but by divine art,

a thick pitch was boiling there below, which belimed the bank on every

side. I saw it, but saw not in it aught but the bubbles which the

boiling raised, and all of it swelling up and again sinking compressed.

If it's open, Bar

Arsenale is the perfect place to sit down and unwind while

taking in

the view. If not, we will continue on Fondamenta de Fazza l'Arsenal

that

will lead us to Campo

San Martino and the homonymous church.

|

|

On our way to the church,

we will pass to our right the beautiful Ponte del Purgatorio and the

not so beautiful Ponte de l'Inferno.

|

Ponte del Purgatorio

|

Ponte de l'Inferno

|

Saint Martin of Tours is

a

cosmopolitan saint, a true son of the Roman Empire. Born in 316 in

Sabaria (modern Szombathely in Hungary, near the Austrian border), he

was educated in Pavia, present-day Italy, and became a soldier in the

Roman Army. Drawn to Christianity, the newly

proclaimed legal religion of the Empire, from his youth, Martin was

forced by his

father to join the Roman army as a way to dissuade him from entering

the religious life. In what became the most famous incident of his

life, at the age of 21 he gave half of his cape to a shivering beggar

he encountered at the gates of Amiens in France. He kept the other half

because it belonged to the Roman Army. The relics of the cape were

guarded in France by a custodian called capellanus, a term from which the

words chaplain and chapel derive. The feast of Saint

Martin is celebrated on November 11th. In Venice, a traditional cookie

in the shape of a horse with a rider wearing a cape is baked for this

occasion. The church of San

Martin (Venetian)

or San Martino (Italian) was built in 1550 by Sansovino. Among its

works of arts, there are beautiful pieces by Tullio Lombardo and the

ceiling fresco by Domenico Bruni and

Jacopo Guarana, a remarkable trompe

l'oeil.

|

Campo San Martin

|

San Martin giving his

cape to a beggar

(marble plaque next to

the church)

|

Ponte Storto and church

of

San Martin from Fdm. del Tintor

|

Campo San Martin

|

|

On the façade of

the church of San Martin there is one of the few remaining bocche di leone used by the people

for anonymous denunciations. Another one can still be seen outside the

church of Santa Maria della Visitazione on the Zattere, in Dorsoduro,

and another one in the Doge's Palace. A stone's-throw away from Campo

San

Martin, on Calle del Pestrin off Fondamenta del Tintor, is the

emblematic restaurant Corte Sconta.

One of the best

places in town to enjoy Venetian food.

|

Giardini

We begin our walk at

Ponte de l'Arsenal. We walk on Riva San Biagio

past the Museo Storico Navale and the church of San Biagio. As we cross

the next bridge, Ponte de la Veneta Marina or de le

Cadene, the wide Via Garibaldi will be on our left. Giovanni Caboto,

the New World explorer credited with discovering Canada while at the

service of King Henry VII of England, and his son Sebastiano Caboto,

explorer of

South America, lived in the corner house (Castello 1642).

|

|

Via Garibaldi

|

Caboto

lived

here

|

|

|

Via

Garibaldi was built on a filled-in canal in the Napoleonic period.

Today,

it is not only the commercial hub of this part of Castello, but also

the

gateway to the Giardini Pubblici.

We

will walk to the end of it. Midway

and on our left we will see Corte Nova. This quaint corte, with its two

wellheads, was already depicted in de' Barbari's view of Venice of

1500. Little has changed since then, but you will notice that the gates

at each end of the corte have been removed. Both wellheads date from

the first half of the 14th century. One is in Istrian stone, and the

other, more ornate, in pink Verona marble.

|

|

|

|

Further up Via Garibaldi

and across from the church of San Francesco di Paola, we'll find Il

Nuovo Galeon, a great place to

have fresh and perfectly cooked seafood and succulent pastas in a

friendly atmosphere. The last time I was there, I got looks of horror

and amazement from my British neighbors as I savored a delicious seppie in umido col nero

(cuttlefish swimming in its own ink).

|

|

|

|

We walk to the end of Via

Garibaldi where the

canal begins (Rio de Sant' Anna) and take the fondamenta on the left of

the canal, Fondamenta S. Gioachin. This is a very colorful area of

Venice that exudes local character. We make a left turn at the end of

the fondamenta on Calle drio el Forner that will take us to Fondamenta

del Forner. We cross Ponte Rielo and ahead of us is Calle Ruga where we

turn left; after crossing the campo,

the

street becomes Salizada

Streta. At the intersection with Calle Larga de Castello we turn right.

This takes us to the long bridge of San Piero and to the Campo and Church of San Piero

(San Pietro di Castello in Italian).

|

|

|

Rio de

Sant 'Anna

|

Rielo

and

Ponte Rielo

|

|

|

Fondamenta del Forner and P. Rielo

|

Fdm. San Gioachin

|

San Piero de

Castello was Venice's cathedral until 1807. Its remote location

is

testimony to the distance that for centuries separated the political

power, centered around San Marco, and the Vatican. The citizens of La

Serenissima always felt that they were Venetians first and then

Christians ("veneziani, poi cristiani.")

The free-standing campanile is very easy to recognize from a distance,

not only because is slightly leaning but also because it is the only

one totally clad in white Istrian stone, a work of Mauro Codussi from

the end

of 15th century.

|

|

I visited the church on a

Sunday

morning in the middle of Communion, at the end of the 10 o'clock Mass.

The church was packed like the end of the world was imminent.

Respectfully, I left and sat outside in the beautiful campo, under the

trees. After several days of carrying my photographic equipment around

town for hours on end, my back had reacted with unbearable pain; the

hard wooden benches on Campo San Piero were not helping. Fifteen

minutes passed and hearing intense clapping inside, but seeing no one

coming out of the church, I decided to go in again. A priest was

speaking but I couldn't fully understand what he was saying. I must

have taken ten steps

inside the church when several folks gave me a look that paralyzed me

in my tracks. Trying to find a surface to lean on to alleviate my

backache, I gave two more steps to position myself next to a column and

got the same look again, this time accompanied by a loud shush. I felt

that I had violated some ancient and mysterious rule. I couldn't deny,

after all, that I was a tourist like a million others. I was

embarrassed

and a little perplexed by such unexpected reaction; Venetians are a

very polite and tolerant people. I later learned,

through fliers posted all around this area of Castello, that the

parishioners were honoring and giving thanks to Don Gabriele for seven

and a half years of ministry. I couldn't help but think how typical

Venetian the whole incident was. The parishioners didn't stop me when I

walked in in the

middle of Communion but they objected when I dared to walk during the

priest's farewell. Veneziani, poi

cristiani.

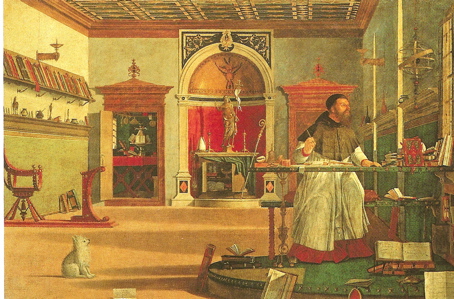

During my wait outside the church I got my reward. A Maltese dog like

the one in Saint Augustine in His

Study

was lying next to me. I felt Carpaccio's ghost sitting on my

shoulder.

|

|

|

In the middle of the

walkway that leads to the main entrance to the church, a white stone

stands out from the rest. This is the place where, according to

protocol, the Patriarch would welcome the Doge when he visited the

church. Not one inch to spare!

We leave the campo by

Calle drio

el Campanile that takes us to Fondamenta and Ponte de Quintavale. After

crossing the bridge, we will be on Rio de Sant' Anna again.

We walk along the fondamenta

to the entrance to the Giardini

Pubblici with

its monument to Giuseppe Garibaldi. The gardens were established at the

beginning of the 19th century, during Napoleon's rule, part on

reclaimed marshland and part on well-established areas. Many historic

buildings were demolished to make way for the gardens. The Giardini

host the Venice Biennale in

several pavilions, each one sponsored by a different country from

Austria to Venezuela, just to mention two.

"Galaxy Forming along

Filaments, like Droplets along the Strands of a Spider's Web,"

by Tomás Saraceno,

Venice Biennale, 2009.

"Galaxy Forming along

Filaments, like Droplets along the Strands of a Spider's Web,"

by Tomás Saraceno,

Venice Biennale, 2009.

From the Giardini we have one of

the most beautiful panoramic views of Venice's skyline. No photo can

capture

the view, especially at sunset when the black silhouettes of La Salute

and San Marco contrast against a crimson sky. Perhaps this is one of

those instances when a few words can say more than a thousand pictures;

especially when they are George Sand's:

"The sun had already set behind

the hills of Vicenza. Great purple clouds were passing over the

Venetian sky. The tower of San Marco, the dome of Santa Maria and the

nursery-garden of spires and steeples rising from every corner of the

city stood out as black needles against the sparkling horizon. The sky

turned by subtle gradations from cherry red to cobalt blue while the

water, smooth and clear as a mirror, faithfully reproduced its infinite

iridescence; it lay like a vast sheen of copper below the city. Never

have I seen Venice more beautiful and enchanted. Its black silhouette,

cast between the sky and the glowing waters as on to a sea of fire,

seemed to be one of those sublime architectural aberrations the poet of

the Apocalypse must have seen floating on the shores of Patmos as he

dreamt of the New Jerusalem and likened it in its beauty to a newly wed

bride." George Sand, 'Lettres

d'un Voyageur.'

|

Inside

the

Giardini we take Paludo San Antonio which will lead us to the

district of Sant' Elena. This

is one of the newest areas of

Venice. Contrary to what many people, Venetians and travel-book

writers included, may say, this is an enchanting area of

Venice. Granted that there are no impressive palazzi or works of art to

admire, but Sant' Elena is only a short vaporetto ride away from all

that, while its residents have the luxury of enjoying a lush

and quiet surrounding, away from the mass of tourists. As you walk on

Viale Quattro Novembre on a sunny summer

afternoon, underneath the refreshing tree canopy, you can enjoy the

spectacular view of the Bacino di San Marco on one side, framed by a

backdrop of distant islands, and on the other, amid unpretentious

but pleasing architecture, the many little gardens with rosebushes and

oleanders in bloom.

We make a left turn on Viale Piave. This takes us to Ponte Sant' Elena

and to the austere church of Sant' Elena.

|

|

Many places around the

world are named after Saint Helena, Constantine

the Great's mother and the godmother of Christianity, but this tiny

area of Venice is the real deal. Forget the Saint Helens of volcanic

proportions or the Saint Helenas of Napoleonic and Napa-Valley fame,

the unassuming church of Sant' Elena, almost falling off the map of

Venice, is the only place that deserves to be called such, as it houses

the relics of the saint. Her remains are displayed in a glass

sarcophagus in one of the side chapels to the right of the entrance.

Dressed in a golden gown she wears a mask and slippers. As I sat all by

myself in the deserted church in front of her relics, I felt 1500 years

of history condensed in one spot, as I pondered how one

single woman could have so dramatically changed the faith, and in so

doing, the fate of the Western world.

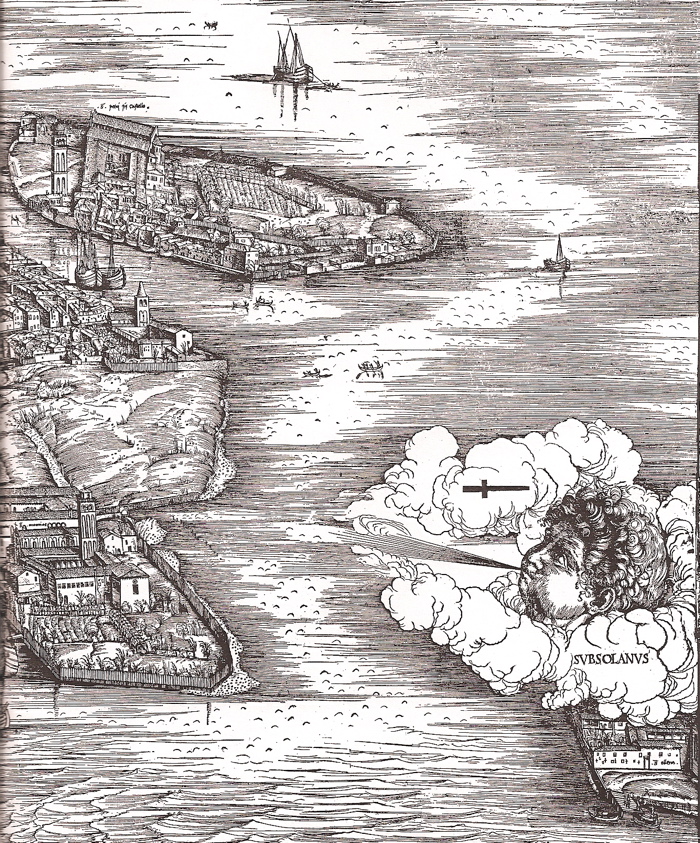

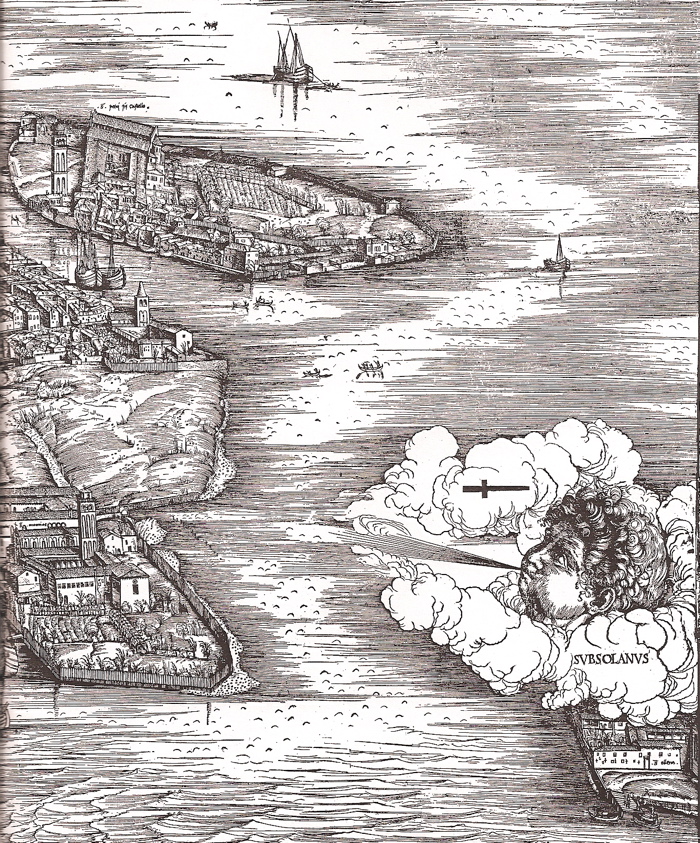

The picture below is the right bottom corner of de' Barbari's

map. Below the Subsolanus wind, barely discernible is only half of the

façade of Sant' Elena, indicating the lack of importance of this

peripheral area. The island was cut off from the rest of Venice.

|

|

The church, originally

founded in 1175, underwent many transformations.

It was deconsecrated by the French and reopened more than a century

later in 1929. Its campanile, demolished when the church was closed,

was rebuilt in 1958.

|

We leave the church and

after

crossing the beautiful Parco delle

Rimembranze,

we go

back to the Riva. In front of

the

Giardini is the monument to the Partigiana,

a moving bronze at

water level created by artist Augusto Murer in the 1960s to honor the

Venetian women of the resistance who fell during World War II.

We cross Ponte San Domenego and

take Riva dei Sette Martiri (named after seven Venetians shot by the

Nazis) on our way back to San Marco. To our right are the twin

entrances

to La Marinarezza, a housing

project first built in 1335.

|

From Ponte de San

Domenego

|

Casa della Marinarezza

|

|

During the winter month,

the Riva hosts an amusement

park. The rides used to be closer to San Marco and now are closer to

the Giardini. It's the perfect place for a lively stroll on a sunny

Sunday afternoon.

|

Summer or Winter, sunny or

cloudy, one thing is certain, this area of Venice is always delightful.

|

This completes our tour of

Castello.

|

|